Introduction

Images of the Emperor and members of the imperial family were the most ubiquitous symbols of Roman power. As an emanation of the central authority, they were designed to embody the ideals of Rome and disseminated to communicate them throughout the territories of the Empire, encompassing all media (from sculpture to painting and coinage). The reproduction of imperial images on such a large-scale meant that they had a simple and important unifying value: the Emperor’s likeness would be recognised in all corners of the Roman world. The production of imperial portraits involved the creation of common models (or types) and the replication of copies for use and distribution throughout the Empire; this process was controlled by the central administration, based on the introduction of new types at subsequent stages of each Emperor’s reign, possibly marking special occasions and celebrations.

However, we know very little about how models were transferred and replicated. It is believed that images were disseminated and circulated as a result of natural dynamics dictated by the art trade and driven primarily by the principle of supply and demand, which may have relied on networks of local workshops. Moreover, we do not know whether this ‘production model’ is valid for all the imperial portraits produced across the Roman world. The distinction between different types of portraits of the same Emperor is sometimes hard to define and it can be difficult to discern between imperial family members and private individuals who simply looked like them or were following imperial fashions. Above all, not all the existing portraits found across the provinces fit perfectly into the identified typologies. The genesis of specimens deviating from the metropolitan models, which are regarded as ‘unique pieces’ or ‘uncanonical’ portraits, could depend on multiple factors: the lack of up-to-date models to work from, the absence of craftspeople with appropriate levels of skill, the individual discretion of a local artist, the demands and preferences of the patron who commissioned a portrait. So these provincial creations can probably be explained as products of local workshops too.

The RESP project's approach

Sculpture and coinage

Two images of Emperor Nero and his mother Agrippina compared (AD 54-59): a marble relief from the Sebasteion of Aphrodisias in Caria (left: http://aphrodisias.classics.ox.ac.uk/sebasteionreliefs.html#prettyPhoto; © New York University Excavations at Aphrodisias, photo G. Petruccioli) and the reverse design of a bronze coin minted in Magnesia ad Sipylum, Lydia (right: https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/type/65360)

RESP is the first research project that tackles these long-standing scholarly questions with a sustained comparative study of Roman provincial art and material culture, focusing on two classes of materials in particular: coinage and sculpture. Through an extensive survey and analysis of the vast archaeological evidence that reflects the many different realities of the Empire, from west to east, the research adopts a new bottom-up approach to the ‘romanisation’ debate: it bridges the scholarly gap between works that have investigated the forms and significance of imperial representations from a primarily ‘romanocentric’ point of view and the still underdeveloped field of studies on provincial material culture. The analysis of the imperial representation, especially on public media (monuments and coins), gives the unique opportunity to look at a well-defined range of visual themes and typologies from different perspectives, comparing Rome and the provinces on a global scale and for a long and continuous period of time.

The other novelty of this approach rests in taking coinage as the point of departure of this investigation to interrogate and reassess sculpture and other classes of materials. Roman provincial coins were produced by hundreds of cities across the Empire over a period of around three centuries, from the rise of Augustus (c. 31 BC) to the administrative reforms of Diocletian (c. AD 297). Featuring the Emperor’s portrait on the obverse and the city’s name and designs on the reverse, they are readily datable and have a definite provenace. Their imagery form the largest existing archive of Roman provincial visal culture, which offers a unique resource for studying the modes and tropes of imperial representation in these territories. To study and process this sheer mass of data the RESP research relies primarily on the catalogues generated by the Roman Provincial Coinage international research project (RPC), both the printed volumes and the online database hosted by the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford: https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/. The integrated analysis of coinage and other materials, primarily sculpture, underpins the RESP research plan, which proceeds in two parallel directions. One strand focuses on the study of the imperial representation in the provinces in full-figure, the other on the study of provincial portraiture.

The Emperor in the civic landscape

The imperial family

The adoption of Emperors Antoninus Pius by Hadrian, with Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (AD 138), depicted on a marble relief of the great altar from Ephesus. © Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna: https://www.khm.at/objektdb/detail/51913/

This research strand investigates how the Emperor, the Empress and the other members of the imperial family were represented in full-figure in the provinces, comparing the extensive evidence of the reverse designs on provincial coins with sculptural representations in relief and in the round.

In the first place, it studies the visual language designed to honour the imperial family within the city’s cultural landscape and how it varied in time and space, to commemorate imperial anniversaries, adoptions and weddings, to celebrate their military achievements and to worship them, interpreting the relationship between the Emperor and the divine through the lens of local religious and cultural traditions.

Secondly, it compares the modes and tropes of imperial representation in the provinces with the iconographic patterns of imperial representation in the official imagery of metropolitan art, especially of imperial coins and medallions and of monumental reliefs in Rome and in Italy. This comparison will show which patterns were inspired by imperial models and which ones depended on regional or local trends, reflecting the cultural diversity of the provincial communities. This study is key also to our understanding of the reception and reinterpretation of the imperial ideology in the art and visual culture of the provincial world: it will show whether these patterns were influenced by changes in the imperial policy or reflected the way in which local administrations engaged with members of the imperial family, or again resulted from the negotiation between both.

All the Emperor’s faces

Rome and the provinces

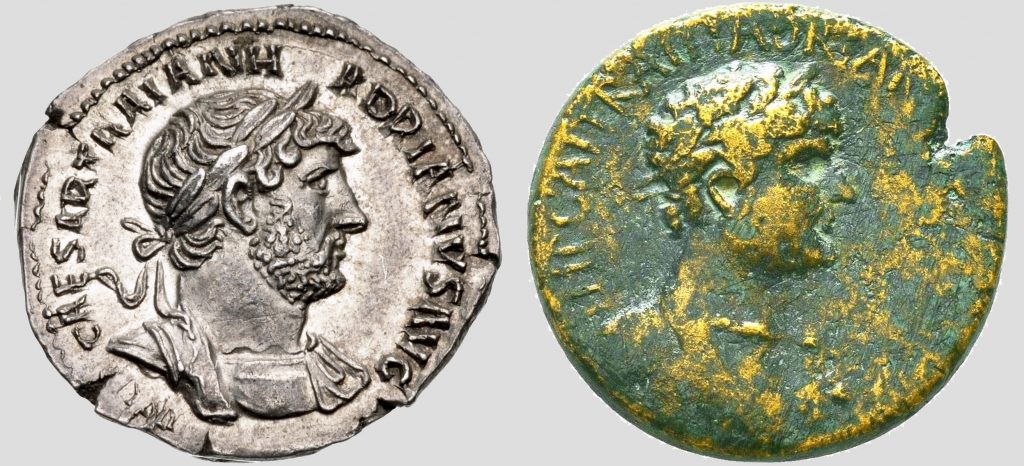

Two portraits of Emperor Hadrian compared (AD 121-123): a silver denarius minted in Rome (left: http://numismatics.org/ocre/id/ric.2_3(2).hdn.567-571) and a bronze coin minted in Sinope, Pontus (right: https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/type/9733)

This strand of research investigates whether and to what extent the imperial portraits made in the provinces conformed to their metropolitan prototypes. The historian Arrian of Nicomedia once described an image of the Emperor Hadrian displayed in the city of Trapezus in Pontus (province of Galatia and Cappadocia): ‘Your statue, which is there, has merit in the idea of the figure, and in the design, as it represents you pointing towards the sea; but it bears no resemblance to the original, and the execution is in other respects but indifferent. Send therefore a statue worthy to be called yours, and of a similar design to one which is there at present, as the situation is well-calculated for perpetuating, by these means, the memory of any illustrious person’ (Periplus I, 3-4). This episode attests that the mismatch between metropolitan and provincial sculpture could be seen as an issue even in antiquity, at least amongst well-educated, visually-literate individuals. The study of sculptural portraits confirms that the specimens of known provenance, which cannot be comfortably assigned to one specific typology, come mostly from the provinces.

The RESP project takes Roman provincial coinage as the starting point to tackle these interpretive problems from a new perspective. It considers all the imperial portraits featured on provincial coins to produce the first systematic typological study of provincial portraiture. The analysis of numismatic portraits shows that the degree of adherence from metropolitan models varied a lot, from exact copies of the reference types to local creations. The numismatic typology of each Emperor in the different regions of the Empire can then be used to re-examine sculptural portraits of uncertain attribution or identification, either found in the provinces or of unknown provenance, and reconsider the traditional interpretation of their genesis and production. The aim of this investigation is ultimately also to understand to what extent the process of dissemination of the imperial image in the provincial territories entailed that the two large industries of sculpture and coinage were interconnected.

The other novelty of this approach rests in taking coinage as the point of departure of this investigation to interrogate and reassess sculpture and other classes of materials. Roman provincial coins were produced by hundreds of cities across the Empire over a period of around three centuries, from the rise of Augustus (c. 31 BC) to the administrative reforms of Diocletian (c. AD 297). Featuring the Emperor’s portrait on the obverse and the city’s name and designs on the reverse, they are readily datable and have a definite provenace. Their imagery form the largest existing archive of Roman provincial visal culture, which offers a unique resource for studying the modes and tropes of imperial representation in these territories. To study and process this sheer mass of data the RESP research relies primarily on the catalogues generated by the Roman Provincial Coinage international research project (RPC), both the printed volumes and the online database hosted by the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford: https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/. The integrated analysis of coinage and other materials, primarily sculpture, underpins the RESP research plan, which proceeds in two parallel directions. One strand focuses on the study of the imperial representation in the provinces in full-figure, the other on the study of provincial portraiture.

Three-dimensional imaging and visualisation

The Roman Emperor in 3D

A 3D scanning session of a bronze head of Hadrian at the British Museum (Department of Britain, Europe and Prehistory) performed by the WMG engineering team (https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/sharing-practice/staff/all-projects/)

RESP combines the traditional approach of typological studies on Roman imperial portraiture with the use of 3D technology to understand the relationship between provincial visual and material culture and their metropolitan models. High-definition imaging and 3D visualisation are used to compare and integrate the data from coinage and sculpture to reconstruct whether portraits on different media derived from the same model or from different ones. Both coin portraits and sculptural portraits are 3D scanned to generate digital models in the round that can be compared and juxtaposed with each other. The comparisons are based on both empirical factors (digital measurements of proportions and key-facial features) and distinctive stylistic characteristics. 3D visualisation is also used to enhance our understanding of differences between coin and sculptural portraits derived from different technical and artistic procedures (engraving vs carving). This process aims to show where stylistic and technical analogies can be demonstrated and whether they reflected the systemic (or occasional) use of shared models between minting and sculptural workshops in the same regions. The ultimate purpose is to identify patterns of behaviour that reflect how and to what extent the manufacture and dissemination of portraits varied geographically and chronologically. This method has two additional advantages: the potential to reconstruct the genesis of coin portraits by tracing and retrieving the potential source of inspiration (the model) from one or more of its derived copies; the potential to recreate both the maker’s and the viewer’s perceptions of ancient visual media, for instance by giving insights into the technical differences between the process of engraving and that of carving to transfer the same portrait type into two different materials and classes of objects.